OU leads study of Ukrainian genetic diversity

Published in the journal GigaScience, the study contributes to an international effort to map the entire pattern of human genetic variation across the world.

Led by a group of Oakland University researchers, the largest study of genetic diversity in Ukraine has been published in the open science journal GigaScience. The study provides data on genetic variants associated with human health and describes historical factors that helped give rise to remarkable genetic variation in a part of the world that has been underrepresented in genome research. The project was an international effort that brought together researchers from Ukrainian institutions, headed by Uzhhorod National University, as well as institutions in the U.S. and China.

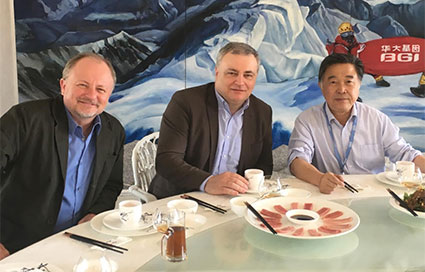

Taras Oleksyk is the lead author of a new study documenting genetic diversity

in Ukraine. In addition to OU, the project involved researchers from Ukrainian

institutions, headed by Uzhhorod National University, as well as institutions in

the U.S. and China.

“Our study shows there is significant genetic diversity in Ukraine, a country that had not been prioritized in genome surveys,” said Taras Oleksyk, assistant professor of biological sciences, and the study’s lead investigator. “We found more than 13 million genetic variants among the DNA samples — nearly 500,000 of which were previously undocumented.”

Along with providing genetic data specific to Ukraine, the study also contributes to the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP), an international effort to map the entire pattern of human genetic variation across the world. Building this map has entailed numerous global surveys of individual genomes in a variety of geographic regions and populations. However, notable gaps have remained, including in Eastern Europe and the Eurasian Steppe.

Among the missing pieces was Ukraine, the largest country located fully in Europe, with a population that was formed through thousands of years of migration and genetic admixture. This territory served as the historic and prehistoric crossroads for the spread of humans throughout Europe and into Asia. Migration events here included the expansion of modern humans into Neanderthal lands, the movement of nomads and early farmers just starting to domesticate plants and animals, the great migrations of the Middle Ages, as well as commercial and cultural transactions along the Silk Road.

|

Ukraine: A key piece of the human diversity puzzle Although the nation was once thought to lack genetic relevance, the study shows that Ukrainians represent roughly a quarter of all genetic variation documented in Europe. |

This broad sweep of human experience has shaped the genomes of Ukrainians and other peoples to the present day, Oleksyk explains.

“As humans moved across the world over millennia, they gained genetic mutations, often due to adaptation to their specific environments,” he said. “These mutations have been passed down through generations, so when we look at genomes of Ukrainians and other populations, what we see is a reflection of their unique evolutionary histories.”

As part of its focus on Ukrainians’ genetic diversity, the study also identified medically relevant mutations whose prevalence differed significantly compared to other European genome sequences openly available through the HGDP.

Compared to the other Europeans, Ukrainians in the study had significantly fewer carriers of specific mutations linked to breast cancer and Leber Congenital Amaurosis, a rare inherited eye disease. Another mutation, known to inhibit a drug used to treat bone disorders, was also less prevalent in the Ukrainians. However, they more often held a mutation associated with autism.

These findings contribute to a growing body of knowledge that could help clinicians assess the medical needs of specific geographic areas and populations.

“With a deeper understanding of how mutations factor into disease, doctors can tailor treatments to people’s genetic profile,” said Oleksyk. “That’s why it’s important to have detailed descriptions of the world’s genomes. This knowledge could profoundly impact human health, and even save lives.”

From left: Taras Oleksyk, Volodymyr Smolanka and Yang Huanming, co-

founder and chairman of BGI, which provided sequencing services for the

Ukrainian genome study. Photo is from 2017 when the three met at BGI

headquarters in Shenzhen, China to discuss the planning of the project.

January 14, 2021

January 14, 2021